Should The Federal Government Give Money To Colleges

These data have been updated. The latest research is available here.

Overview

States and the federal government have long provided substantial funding for higher pedagogy, but changes in recent years have resulted in their contributions being more than equal than at any fourth dimension in at least the previous 2 decades. Historically, states have provided a far greater amount of assistance to postsecondary institutions and students; 65 percent more than than the federal government on average from 1987 to 2012. But this difference narrowed dramatically in recent years, particularly since the Corking Recession, as state spending declined and federal investments grew sharply, largely driven by increases in the Pell Grant program, a need-based financial aid program that is the biggest component of federal higher teaching spending.

Although their funding streams for higher education are now comparable in size and have some overlapping policy goals, such as increasing access for students and supporting research, federal and country governments aqueduct resource into the system in different ways. The federal authorities mainly provides financial assistance to individual students and specific research projects, while country funds primarily pay for the general operations of public institutions.

Policymakers beyond the nation face hard decisions about higher instruction funding. Federal leaders, for example, are debating the future of the Pell Grant programme. The Obama administration has proposed increasing the maximum Pell Grant award to keep pace with inflation in the coming years, while members of Congress take recommended freezing it at its current level. State policymakers, meanwhile, are deciding whether to restore funding after years of recession-driven cuts. Their deportment on these and other critical problems will help decide whether the shift in spending that resulted in parity is temporary or a lasting reconfiguration.

In a constrained financial environment, policymakers also will demand to consider whether there are meliorate ways of achieving shared goals, including pupil admission and support for enquiry. Such approaches could entail more coordination, other funding mechanisms, or policy reforms. In addition, it volition be necessary to recollect almost the implications of parity and whether funding strategies volition require changes in guild to attain desired outcomes. This chartbook is intended to provide a starting betoken for answering such questions past illustrating the existing federal- state human relationship in college didactics funding, the way that human relationship has evolved, and how it differs beyond states.

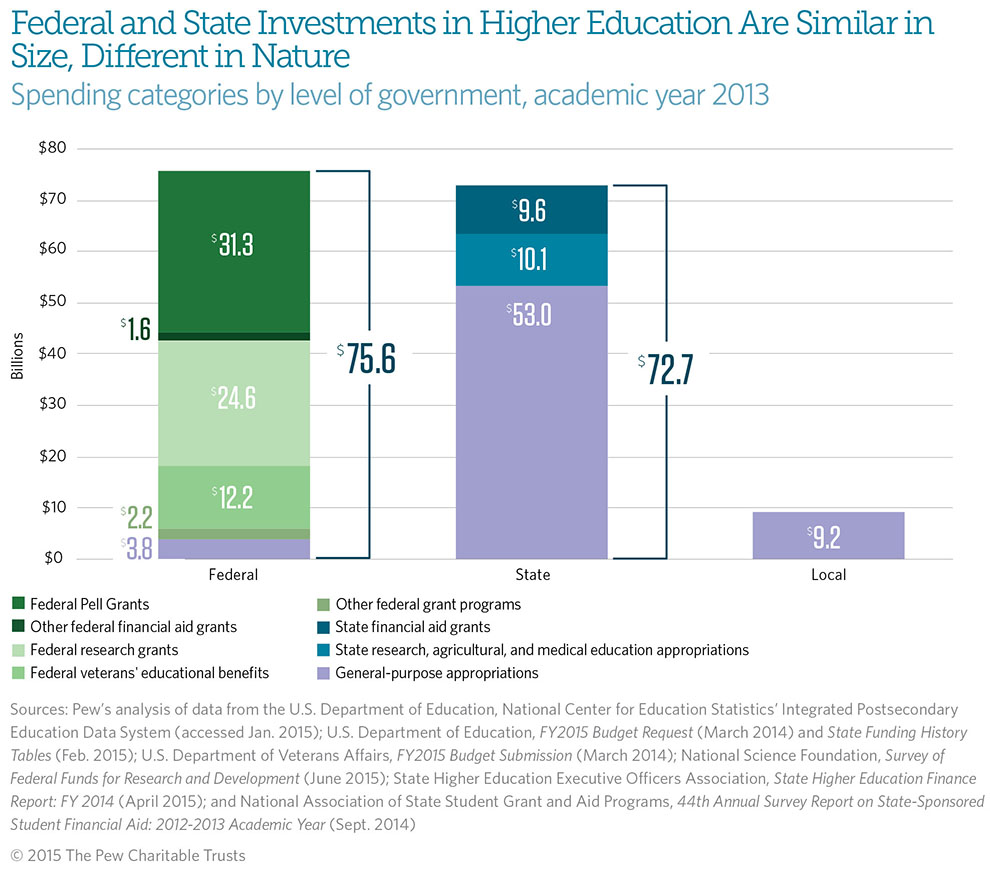

Figure one

Though only about 2 percent of the full federal budget, higher education programs make upwardly a large share of federal education investments. For instance, well-nigh half of the U.Due south. Section of Education's budget is devoted to higher education (excluding loan programs). College education funding also comes from other federal agencies such as the U.S.Departments of Veterans Affairs and Wellness and Human Services, and the National Scientific discipline Foundation.

College education was the third-largest area of land general fund spending in 2013 behind One thousand-12 instruction and Medicaid.

Figure two

In 2013, federal spending on major higher instruction programs totaled $75.6 billion, state spending amounted to $72.7 billion, and local spending was considerably lower at $9.ii billion. These figures exclude student loans and college education-related tax expenditures.

Although the federal and state funding streams are comparable in size and have overlapping policy goals, such as increasing admission for students and fostering research, they support the higher education arrangement in different ways: The federal government mostly provides financial assistance to individual students and funds specific research projects, while states typically fund the full general operations of public institutions, with smaller amounts appropriated for research and financial aid. Local funding of $9.2 billion largely supports the general operating expenses of customs colleges. For more information, see Appendix A.

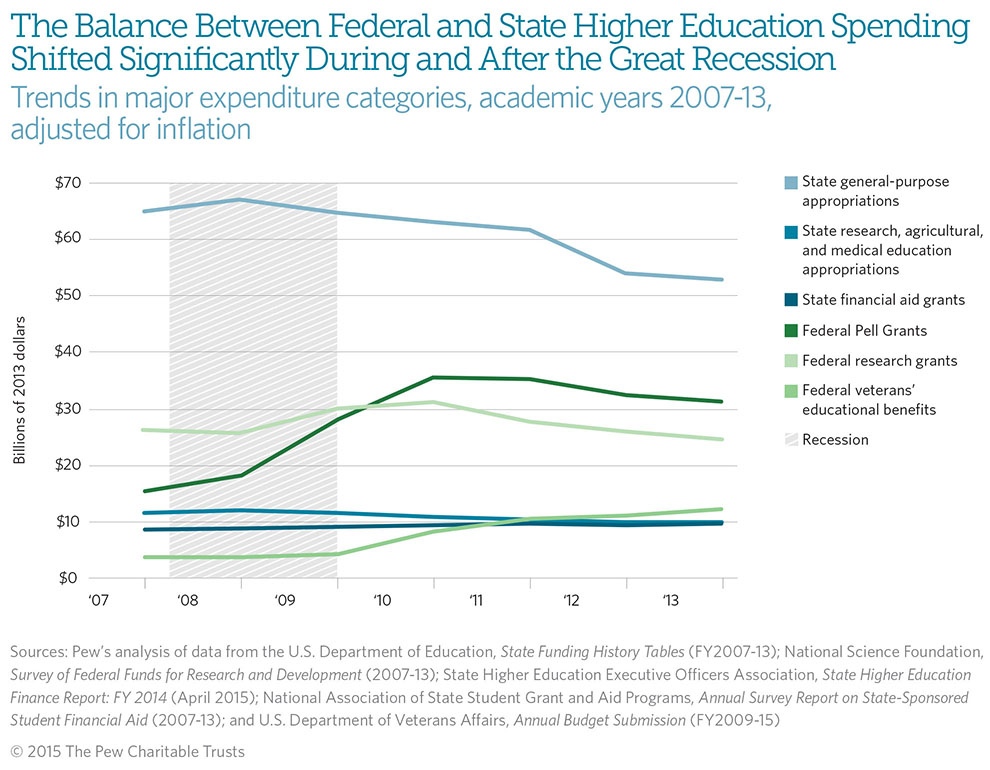

Effigy three

Funding for major federal college teaching programs grew significantly from the onset of the recession, even as country support brutal. The federal spending areas that experienced the almost significant growth were the Pell Grant programme and veterans' educational benefits, which surged by $13.2 billion (72 percent) and $8.4 billion (225 percent), respectively, in real terms from 2008 to 2013. The biggest decline at the state level was in full general-purpose appropriations for institutions, which cruel by $fourteen.1 billion (21 percent) over the same period. During those years, the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) students grew by 1.2 million (8 per centum). For more information, see Appendix A.

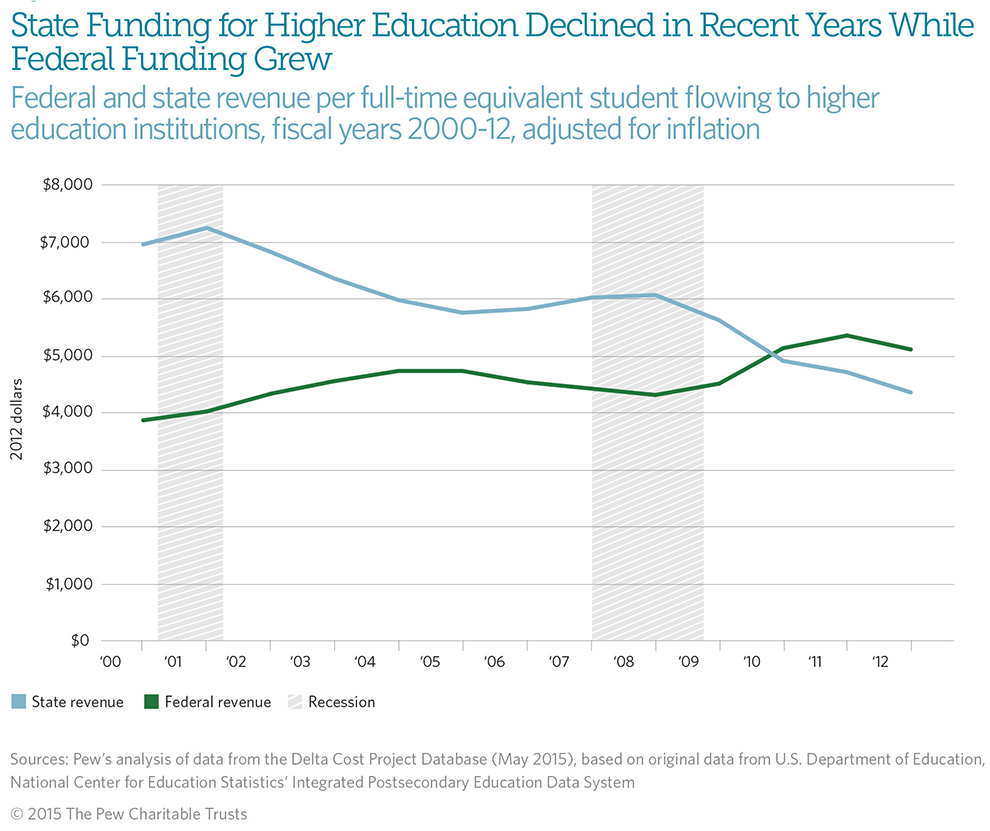

Figure 4

A major shift has occurred in the relative levels of funding provided by states and the federal government in recent years. By 2010, federal revenue per full-fourth dimension equivalent (FTE) student surpassed that of states for the first fourth dimension in at least two decades, after adjusting for enrollment and inflation. From 2000 to 2012, revenue per FTE student from federal sources going to public, nonprofit, and for-profit institutions grew by 32 per centum in real terms, while state revenue fell by 37 percent. The number of FTE students at the nation'due south colleges and universities grew by 45 per centum during the same menstruation. Without adjusting for enrollment growth, full federal revenue grew past 92 percent from $43.3 billion to $83.2 billion in real terms, while country revenue brutal past 9 percent from $77.8 billion to $70.8 billion afterward adjusting for inflation.

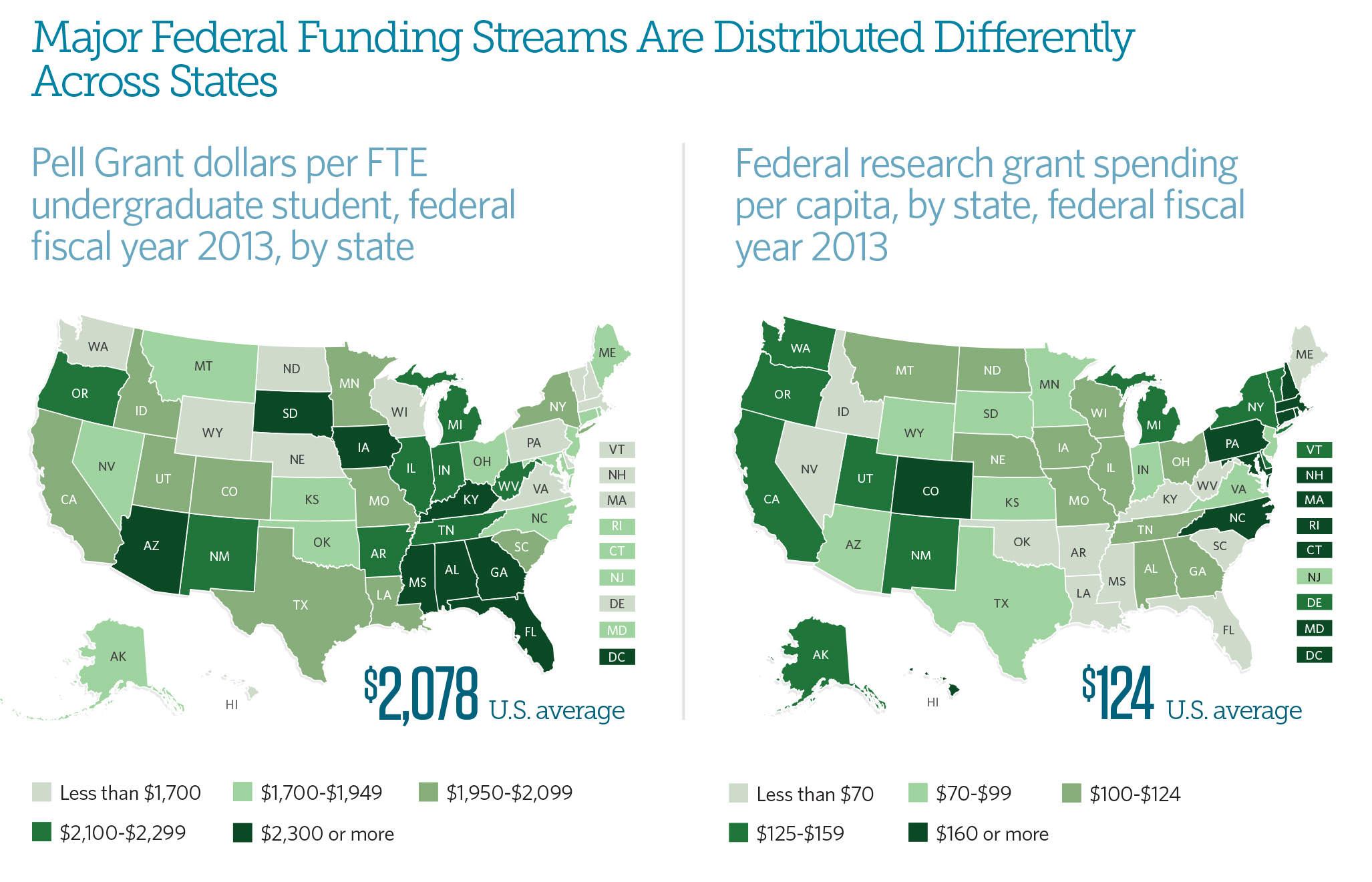

Figure 5

Total federal college education funding varies widely across states, and the major types of funding accept very different geographic distributions. For example, Pell Grant funding, which is distributed based on a calculation of students' financial demand, ranged from $1,177 in North Dakota per FTE undergraduate to $3,401 in Arizona, compared with a national average of $2,078. High Pell Grant states are full-bodied in the Southeast.

Similarly, per-capita federal research funding ranged from $37 in Maine to $476 in the District of Columbia, compared with a national boilerplate of $124. States with loftier levels of research back up are concentrated in the Northeast. Run across Appendix A, Figure 2 for more information about federal funding categories.

Figure half dozen

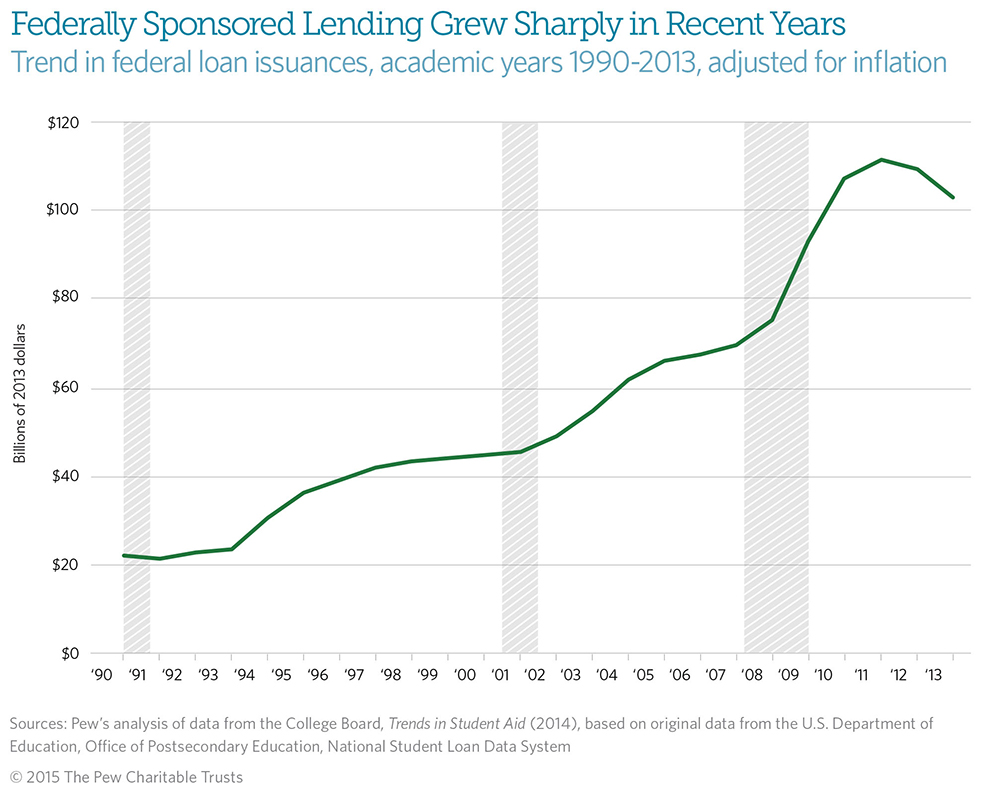

The federal government is the nation's largest pupil lender; it issued $103 billion in loans in 2013. States, by dissimilarity, provided only $840 million in loans that year, less than i pct of the federal amount.

Although they must be paid back with interest, federal loans let students to infringe at lower rates than are available in the private market. Federal loans grew 376 percentage between 1990 and 2013 in real terms, compared with enrollment growth of 60 percent. These figures correspond the book, rather than the cost, of those loans.

Figure 7

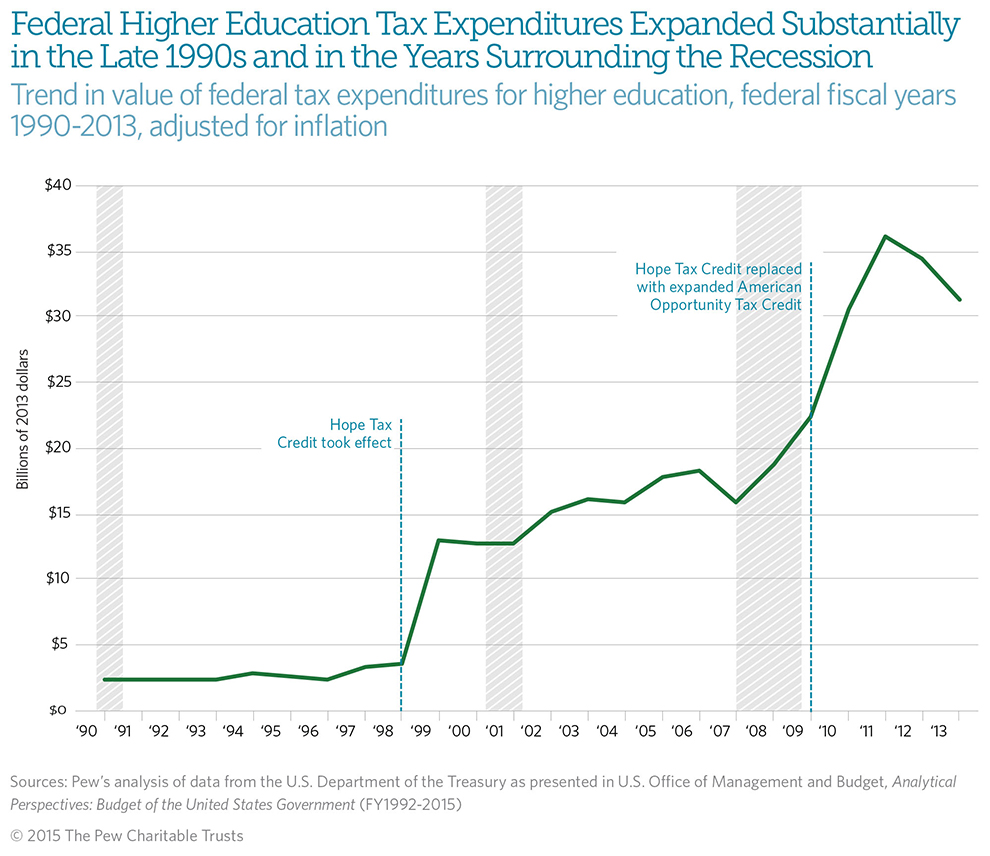

The federal government likewise supports higher education through the taxation code. In 2013, it provided $31 billion in tax credits, deductions, exemptions, and exclusions to offset costs, substantially equal to the $31 billion information technology spent for Pell Grants. Because these expenditures allow taxpayers to reduce their income taxes, they reduce federal revenue and are similar to directly government spending.

The value of federal tax expenditures for higher education is $29 billion larger than it was in 1990 in real terms. Much of the growth coincided with the creation of the American Opportunity Tax Credit (formerly Hope Revenue enhancement Credit) in 1997 (constructive 1998) and its expansion and renaming in 2009. Between 1990 and 2013, the number of FTE students grew by 60 per centum.

Figure eight

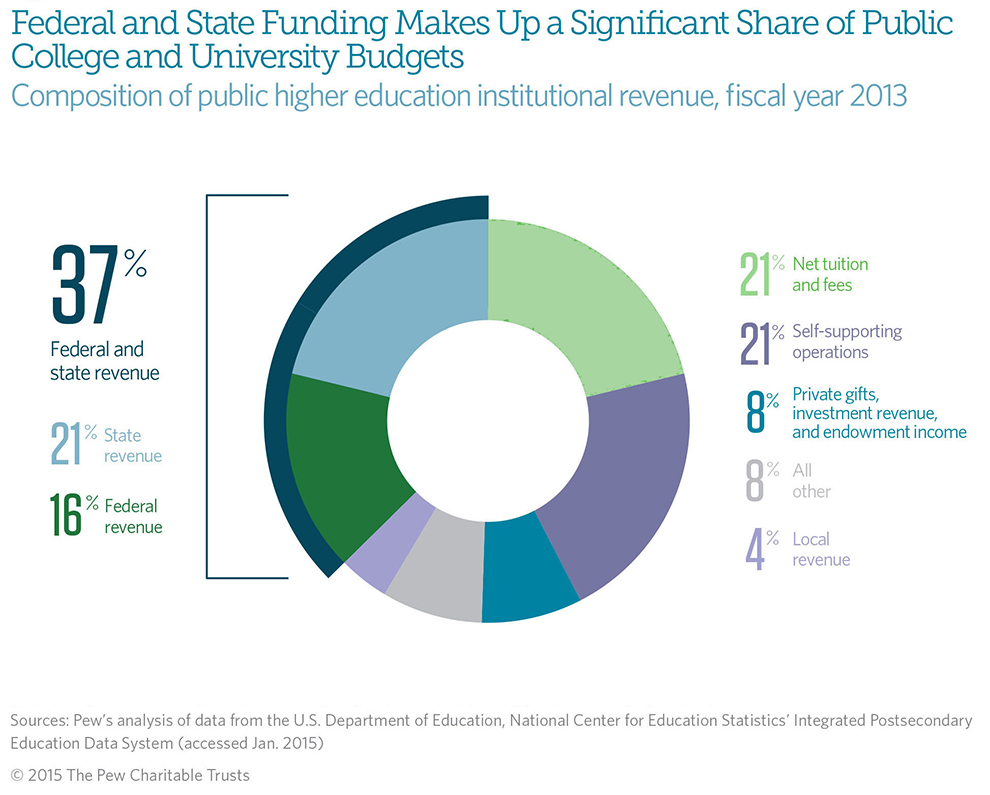

Public colleges and universities brainwash 68 percent of the nation's postsecondary students. Ninety-viii percentage of country and 73 percent of federal college education funding flows to these institutions. Acquirement from federal and state sources fabricated up 37 percent of total acquirement at public colleges and universities in 2013.

Effigy 9

The total corporeality and mix of acquirement used for higher instruction vary beyond states. Per-FTE-educatee revenue flowing to public institutions from federal sources ranges from $iii,465 in New Jersey to $10,084 in Hawaii, and from country sources spans between $three,160 in New Hampshire and $nineteen,575 in Alaska. Other elements, such as the amount of revenue from tuition, besides differ.

Federal funding variation stems from differences in students' fiscal needs and in the types of inquiry conducted in each state, among other factors.

The range in state funding is due, in role, to policy choices regarding college didactics. For case, North Carolina'due south and Wyoming's constitutions stipulate that public institutions should exist equally close to free as possible, and schools in both states receive above-average land revenue and below-average internet tuition revenue.

Source: https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/issue-briefs/2015/06/federal-and-state-funding-of-higher-education

Posted by: gobeilrappy1958.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Should The Federal Government Give Money To Colleges"

Post a Comment